After the blockbuster James Harden trade from the Houston Rockets to Brooklyn Nets, Rockets General Manager Rafael Stone half-joked in a press conference that you couldn’t judge the trade until 2030 given the future draft capital the Rockets received. Stone and the Rockets made a long-term investment – exchanging James Harden for potentially valuable future assets. We won’t know how valuable for years.

As wealth managers that oversee our clients’ investments, we can relate to both the question and answer in this dialogue. In our business, it’s not uncommon for clients to ask about timeframes for measuring success.

As wealth managers that oversee our clients’ investments, we can relate to both the question and answer in this dialogue. In our business, it’s not uncommon for clients to ask about timeframes for measuring success.

To answer that question, we start with what we are trying to accomplish. At Heritage, we build long-term portfolios using ten-year risk and return assumptions (with adjustments along the way). So, it makes sense (on paper) to suggest that ten years is a reasonable evaluation period. But in reality, we know that’s unrealistic. Because no one will pay you for a decade without judging you.

But measuring investment success over a few weeks, months, or even a couple of years is also unrealistic. So, let’s bridge the gap and figure out how long to give an investment strategy before making a judgement.

Why Investment Strategy Patience Matters

First, let’s touch on why patience matters by seeing what investment impatience looks like and why you want to avoid it.

Investment impatience is moving from one strategy to another for short-term performance reasons. It means selling investments, paying fees, paying capital gains taxes, and reinvesting lesser dollars somewhere else. Some investments will be in tax-deferred retirement accounts where capital gains aren’t an issue, but it’s rare for that to be your entire investment portfolio.

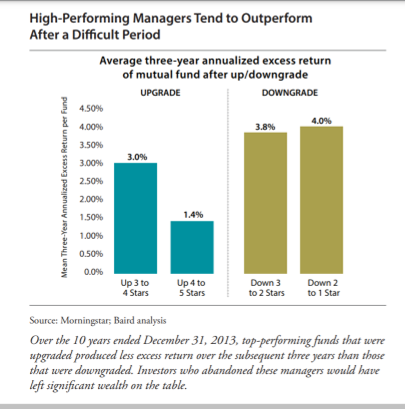

It also means abandoning an investment or a strategy and possibly missing a performance rebound. In a study referenced below, Baird’s Asset Manager Research team found that top performing mutual funds that had underperformed their peers for a period of time subsequently went on to outperform after they received a performance based ratings downgrade from Morningstar.

“Most high performing managers can and do make up lost ground and add excess return following periods of weakness, particularly over an intermediate time period.”

We see this time and time again. Someone invests in certain mutual funds because they had strong long-term track records. The funds hit a rough patch. The investor sells, which comes with fees and tax payments. Then buys new mutual funds. Studies show the funds that were sold are highly likely to do well after everyone loses investment patience and dumps them.

We see this time and time again. Someone invests in certain mutual funds because they had strong long-term track records. The funds hit a rough patch. The investor sells, which comes with fees and tax payments. Then buys new mutual funds. Studies show the funds that were sold are highly likely to do well after everyone loses investment patience and dumps them.

So, Do You Really Need to Evaluate?

Consider that your portfolio’s main purpose is turning savings into a bigger nest egg. That means your portfolio is doing its job if it’s providing you the returns needed to make your financial plan work. Beating an arbitrary benchmark over an arbitrary time period should not be your main goal.

For example, if you had decided at the beginning of 2000 that you wanted to beat the S&P for the next ten years, you could have met your goal by earning a total return of -8% over that decade. (The S&P 500 lost 9% from 1/1/00-12/31/2009.) But that probably would have been a setback for your financial plan.

The point? It’s fair to wonder how your investments are doing relative to alternatives. But be careful to not evaluate arbitrarily just for the sake of evaluating.

Here’s where history can help

There are two studies that can help us think through the topic of evaluation. They review how patient to be with a mutual fund and how top mutual fund managers perform against their peers. While not perfect proxies for a diversified portfolio that owns multiple asset classes, they’re instructive on the time periods that should and shouldn’t matter to an investor.

The Truth About Top-Performing Money Managers by Baird’s Asset Management Research.

The Next Chapter in the Active vs. Passive Debate by Fiducient Advisors.

Both concluded that top performing mutual funds experience persistent periods of poor relative performance despite compiling long-term strong track records.

Baird’s study reviewed more than 2,000 mutual funds over a ten year period and focused on funds that outperformed by one percent or more annualized for ten-years with less risk.

“97% of those top managers had at least one three-year period in which they underperformed by one percentage point or more.”

“About half of them lagged their benchmark by three percentage points.”

“And one-fifth of them fell five or more percentage points below the benchmark for at least a three year period.”

They didn’t just do this once, but had multiple three year underperformance spats.

Fiducient looked at the top performing mutual funds in different categories over ten years.

“83 percent of ten-year top quartile mutual funds [funds that performed in the top 25 percent of their category for ten years] were unable to avoid at least one three-year stretch in the bottom half of their peer groups.”

“54 percent of ten-year top quartile mutual funds were unable to avoid the bottom half during a five-year period.”

What Does This Tell Us?

Three years isn’t enough time to judge an investment, or investment strategy. Five years may not be either. Over half the time the top performers in the Fiducient study were in their peer group’s bottom half during a five-year period.

If three and five years aren’t enough, but longer time periods sound more like the Stone/Rockets conversation mentioned earlier, what to do?

Actively evaluate circumstances besides relative investment performance.

It’s fine for a top performing mutual fund to underperform for a few years. Likewise, a well thought out investment strategy can have similar struggles without needing to be changed.

Ask questions to figure out what’s going on

Focus on the following questions and examples related to investments and investment strategy.

1. Has the team’s investment process or approach changed significantly? For example, did you hire a U.S. growth manager who is now investing in value stocks or international stocks? Or did the investment team that built your strategy change their philosophy and approach and are now pursuing a different path?

2. Does the performance you are concerned about match the performance in other similar environments? For example, does the investment always do poorly when markets are speculative? Or does the investment strategy typically underperform when large cap stocks are out of favor?

3. Have there been personnel or organizational changes? For example, did a mutual fund lose a star manager, or did the fund family get acquired? Or were there personnel changes at the firm that built your investment strategy?

4. Has the manager taken on lots of new money that would make it hard to replicate their prior investment success? For example, a manager whose track record was built investing in smaller companies that can no longer do so because they manage too much money to invest in those stocks without moving the market.

If the answers don’t add up, then the question of how long to give an investment strategy changes. Have less investment patience. But if things haven’t changed and the investment or strategy are just facing struggles, it’s been our experience that patience should be rewarded.

One of the most important jobs your wealth manager has is to help you create a financial plan with realistic goals and set an investment approach that maintains focus on that plan – not on keeping up with the Jones.

It might surprise you to hear that, at Heritage, we do a lot of this work on understanding your current financial plan and reviewing your current investments before we are formally hired. It’s how we provide you with an opportunity to road-test working with us. If you aren’t a client of Heritage today, but are interested in taking a test drive, we would love to hear from you.