In honor of America’s birthday, this month’s episode of Wealthy Behavior digs into the history of our country’s banking, currency, and overall economic system, and how key decisions made almost 250 years ago are the drivers of our wealth today. Host Sammy Azzouz is joined by guest and fellow history buff Michael Waldron, Director of Portfolio Management at Heritage Financial, to talk about:

– the first ever U.S. asset bubble more than 200 years ago and how it’s related to our current banking system,

– what the transition to the greenback after the Civil War can tell us about digital currencies today, and

– what role today’s Coast Guard and prohibition played in our current tax system.

An intriguing listen for anyone building wealth, even if you aren’t a history buff yourself.

Check out Sammy and Michael’s top book recommendations on the history of politics, economics, and prosperity in America. https://www.thebostonadvisor.com/best-presidential-biographies/

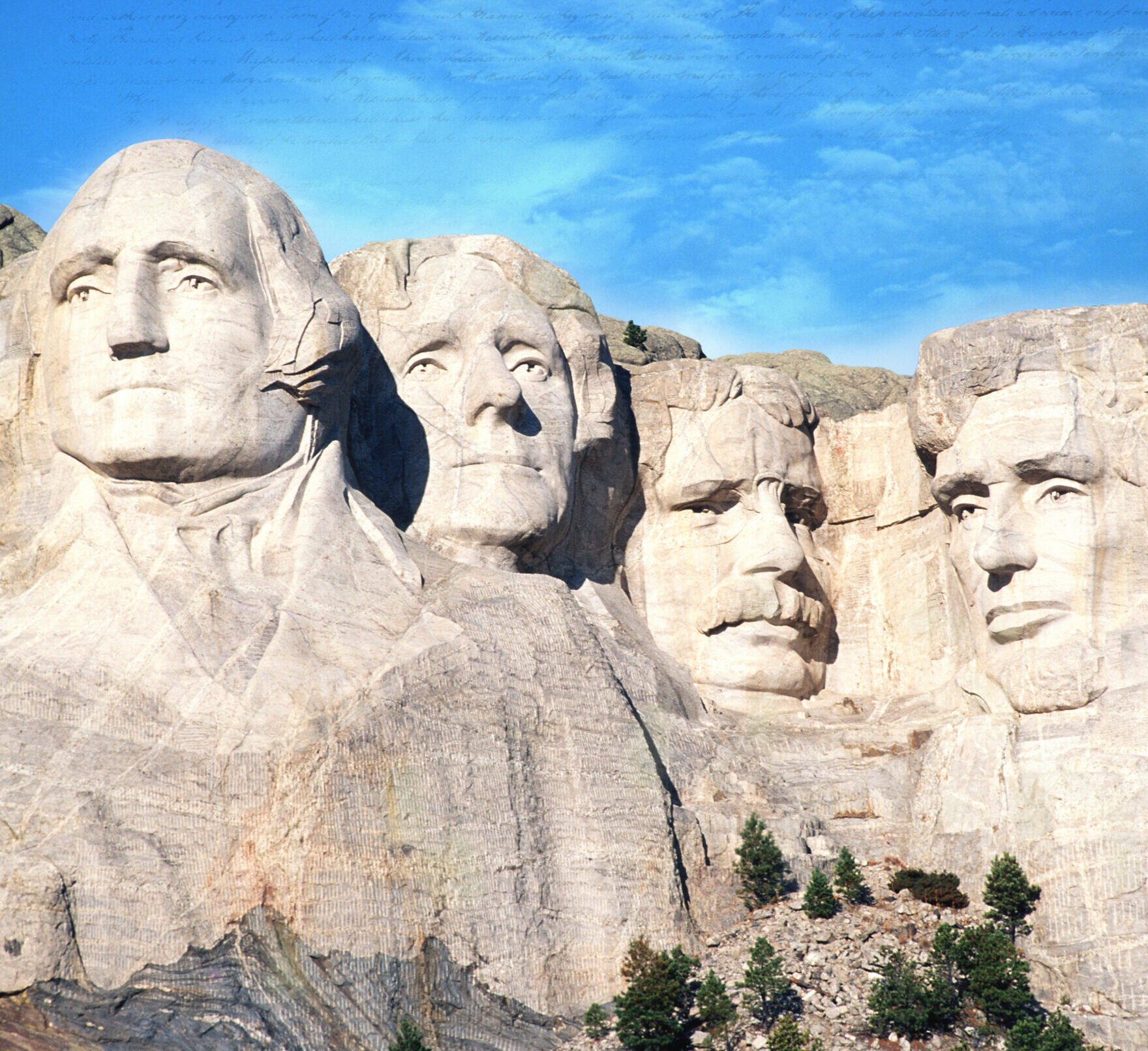

Wealthy Behavior: Presidents and Your Wealth

This automated transcript may contain grammatical errors.

00:00:10 – 00:05:04

Welcome to Wealthy Behavior, talking money and wealth with Heritage Financial. The podcast that digs into topics strategies and behaviors that help busy successful people build and protect their personal wealth. I’m your host, Sammy Azzouz president of Heritage Financial, a Boston based wealth management firm working with business owners, executives and retirees for more than 25 years. Now, let’s talk about the wealthy behaviors that are key to a rich life.

Welcome to another edition of the Wealthy Behavior podcast, talking money and wealth with Heritage Financial. I’m your host Sammy Azzouz and today I’m joined by my colleague, Michael Waldron, Heritage’s Director of Portfolio Management, to talk American presidents and what we learned about finances and our economic history from reading about them. A few months ago, Michael and I collaborated on a blog post at thebostonadvisor.com. We had each just finished reading at least a biography of every U.S. president and we reviewed the books that we read and we decided on a favorite book for each president. Michael and I took different approaches to building our reading list, so it was fun to compare notes. And while it wasn’t the main reason why we read them, these books ended up offering a lot of information on how our country’s financial system was built, our economic history, our current two party system that I think are relevant to investors today. So for the July edition of wealthy behavior, we wanted to share some of that with you. Welcome to wealthy behavior, Michael. Thanks, Sammy. So Michael, in thinking about this, we really could have gone in a lot of different directions and subtopics, but the areas we decided to focus on were the evolution of our banking system and currency, the history of our national debt, and government revenue in the form of tariffs and taxes. Anything else that you felt you wanted to add today? I think that that’s already an agenda that could make up four or 5 podcasts if we wanted it to. Absolutely. And we don’t want to get too far into the weeds here. So let’s start with the banking system because the banking system really starts with pretty interesting stuff. It starts to nasty early debates in our country and kind of leads to the two party system that we have in place today. Because during Washington’s administration, the federalists and the Republicans squared off and battled over Alexander Hamilton, who was the secretary of treasury’s plans for a national bank, what do you remember kind of going through those early biographies of Washington, Jefferson, adding in Hamilton, obviously, who wasn’t a president. What do you remember about our struggles to start a banking system from those books? Yeah, you know, it’s interesting, right? The start of finance with the first bank of the United States is just so interrelated with the interpretation of the constitution. So it gets right back to some of the original issues that our country was dealing with. And that is, do you only have explicit powers given by the constitution or do you have implied powers where something like being given an explicit power to collect revenue gives you the incidental power to have a bank also chartered on the federal level? And there’s a big split there like Sammy said between the federalists, let’s say, sure the government has a heck of a lot more authority to create these things and that’s led by Hamilton versus the more Jeffersonian and southern view of the states have as many rights as possible and the federal government is quite limited in what it should be doing. And there was a concern with that people who espoused that viewpoint that the moneyed interest would become too powerful that the bank would become too powerful and that really we should be more of an agrarian society and not have all those capital structures in place. Yeah, definitely. And I think that that’s also something that, of course, is self-interest. So when we talk about the first bank of the United States, it’s branches are all in the north. It’s Philadelphia. It’s Massachusetts. It’s New York. The IPO that they come out with, which we can go over in a bit, really goes to northerners and some foreigners not so much to the south, and it’s that explodes in value you’re getting the northerners becoming rich, the southerners not. There’s always this view whenever you kind of have the farming agricultural side versus the industrial side, that farmers are borrowers. So moneyed interests, banks, lenders are the ones that are taking advantage of the people who are actually working the land. So I think you see that kind of cut on a geographical line. You have the north’s interest versus the souths interest. Absolutely. And it also created a major rift between George Washington who ended up supporting Hamilton and his view of a national bank and Jefferson and Madison who, in particular Madison was a very loyal Washington ally, Jefferson not so much.

00:05:04 – 00:10:10

I don’t think there’s anybody that Jefferson ever was truly loyal to. He’s literally disloyal to every president he served under and putting out a lot of propaganda about Washington to the point where it was interesting to read Martha Washington basically despised Thomas Jefferson, considered his election a tragedy and didn’t want to see him ever after Washington passed. So we know that Hamilton gets his bank, you mentioned the IPO, which is not what they called it at the time, but talk to me a little bit about that first kind of bubble that we had and the implications of that bank. Yeah, so it’s kind of interesting, let’s think about this bank. This is the early 1790s so the first bank of the United States actually raises $10 million in capital. It seems like such a small amount today but that amount actually was larger than the combined total of the capital of all existing banks. So all existing banks at that time had to be chartered by the state and could only operate in the state that they were existing in. So the national bank was the first that could cut across states. What’s important about this is that America lacked a uniform currency. Every state had its own currency. And this bank as an institution could have something that could be transacted across all of the different states. You also needed some mechanism to be able to collect revenue. This comes immediately after Alexander Hamilton gets through his proposal to assume the state’s Revolutionary War debt by the federal government. So you need to make payments on that debt, you need an institution that can handle it and then things like handling foreign exchange, so instead of having foreign exchange relative to each state’s bank notes, you can do a relative to a U.S. currency, and then it also can extend the credit to both the government and businesses. So the bank raises $10 million, one of the important things is you think about the bank of the United States as a government entity. The government’s a minority owner of it. So the government has about $2 million or 20% of the stock and the remaining stock is held by public investors. So it is a for profit institution, not fully controlled by the government. And anyhow, they go out and they raise this kind of $8 million outside of the two that the government is putting in. And they issue what’s called script and I think the script is maybe the first bubble in U.S. financial markets. So it’s kind of an esoteric topic, but it’s fairly easy to understand. Script was about a $25 down payment that you could put, and it would entitle you to buy a certain par amount of actual equity in the bank. So you put down a fraction, it’s levered borrowing. So they issue script at $25, and then all of a sudden, prices rise, really rapidly and as you get into August of 1791, scripts priced at $300. So you go from 25 to 300, you’ve done over a ten X. And again, those kind of initial offerings where they raise capital, most of that bank stock is held by folks in Philadelphia, Massachusetts, New York, some foreigners. And this is really what sets off kind of the southerners of, “See this is exactly what we thought, you set this up and it’s for the north’s advantage relative to the farmers that are out there working the fields.” And it’s easier to say in hindsight, but it’s obvious that Hamilton had the right argument, basically. Which is ultimately why Washington supported it. You can’t have a functioning economy without capital. Capital being available, without people or lenders being comfortable that the country will pay its debts off, all that that entails without a manufacturing base in a lot of the stuff that Hamilton put in place. And I would say if you’re interested in this and you are thinking of a book to read outside of the presidential biography list, you know, Ron Chernow’s Alexander Hamilton is a must. Absolutely. All right. So the bank bill passes and Washington decides not to veto it based on arguments ultimately that came from Hamilton. But connected to the banking system is this idea of a national currency. And I know you have a lot of thoughts on it. Before the Civil War, basically, correct me if I’m wrong, the U.S. just used gold and silver coins as currency. You know, private banks had their own paper currency in terms of banknotes that they had issued. They were redeemable at the bank’s office, but they only had value basically if you could count on the bank to redeem them, the bank failed, you know, it’s notes were worthless. And by and large, we really didn’t have the current currency that we think of until the Civil War when greenbacks were emergency paper currency issued by the U.S. and they were printed in green on the back.

00:10:11 – 00:15:13

And that they were legal tender, but they were not backed by existing gold or silver reserves. Yeah, no, definitely. And part of that, when you think about a metals-based economy, if you don’t put that in a bank, you don’t expand credit. When you expand credit, you have multiple times the money stock than the physical money that’s in the economy. So when you have this bank coming to existence the first thing that it does is it increases the money supply, which actually is a huge boost to the overall economy instead of thinking about, okay, you just have gold or silver in a chest, you have it in a bank deposit. The bank is making loans of other paper currency out and you’re able to give credit to businesses to farmers to individuals that need money to go and do productive stuff with them. It really kickstarts kind of the economy of the U.S. and really helps us grow into starting to become more of an economic power. Yeah, and do you know why it took ultimately so long to have a paper currency, a national paper currency? So, you know, I would even say that the connection to something to a physical metal really largely survives well into the 20th century. So you do have a paper currency, but the paper currency, because it’s just Fiat, if it has nothing backing it, is subject to so much potential for a manipulation. You back it by something that physically would have to be delivered, if more gets printed, you call that in, you say give me my X number ounces of gold, and you feel like there is an actual value to that in that can’t just be manufactured by a government. So I think it gets to how much trust you have in the system, how deep has the system been able to ingrain itself and as you get later in American history I think that you have financial markets that are developed enough that you can switch to something that’s closer to a Fiat currency. Some folks still question paper money there’s no doubt about that, but certainly when you’re just starting the idea of, okay, I’ll just accept this for what it is you want something of value backing it and I think that just takes time. Yeah, absolutely. And I recall, the continental dollars that they issued during the American Revolution, which quickly lost their value due to inflation, I think, left a bad taste in people’s minds and politically needed to distance ourselves from that experience until people were comfortable accepting a “paper currency” instead of something backed by anything else. Definitely. Any thoughts on currency before I jump ship to a couple books that I think people may enjoy outside of the presidential biographies here? The only thing that I would say a little bit on this is you had mentioned Madison and I think he is a fascinating character between this because Madison is probably one of the founding writers of the federalist papers along with Hamilton. So when they’re passing that first bank of the United States, you actually have Hamilton who’s making his argument reference Madison, who is on Jefferson’s side. So he’s quoting him in Congress and he quotes federalist 44, say, no axiom is more clearly established in law or in reason that whenever the end is required, the means are authorized. Wherever a general power to do a thing is given every particular power for doing it is included. And Madison hitches himself to the Republicans, to Jefferson, afterwards. And then he ends up in a situation where the bank charter is expiring during his presidency, and he actually ends up part of the second bank of the U.S. So he flip flops on both sides, goes from a strong proponent of kind of government’s expanded power to do things that are not explicitly written in the constitution. More towards the Jeffersonian side of your extremely limited on your federal powers and then back again once he’s actually in power. Yeah, funny how that works. I think what Jefferson wanted a limited presidency and ended up doing the Louisiana Purchase and thinking it was unconstitutional, but not caring to get it approved by Congress. So I think one book I’d recommend for folks outside of the biographies is Ways and Means by Roger Lowenstein, Ways and Means Lincoln and his Cabinet and the Financing of the Civil War really talks about kind of the winning the financial battle in the war and introducing the dollar greenback and how we got to that point and a little bit of the taxing history of the country against the backdrop of the war and how the north was able to do things quite a lot better in those areas than the south.

00:15:14 – 00:20:04

I would say around the same period that we’ve been talking about kind of two additional characters are maybe worth reading about on the biography front. One would be Henry Clay, so he kind of picks up as the advocate on the federalist which turns into the wake side. Great biography by Robert Remedy Statements for the Union Henry Clay. And then, of course, I’ll give a plug to Gene Edward Smith and John Marshall. So if you’re interested in some of the constitutional arguments that we’ve been talking about a little bit and how they interpret certain clauses of the constitution, John Marshall, by Gene Edward Smith is a great read. That is my old college professor, Gene Edward Smith, I had him for a couple of college classes. So that’s pretty cool. So getting from there to something that people still talk about and creates a lot of controversy is the level of the national debt and the idea of a national debt. You know, the debt started with Hamilton’s ideas, right? I mean, we started with that in terms of assuming the state debts that were racked up during the Revolutionary War and not handled during the period of the Articles of Confederation, but it’s always been a controversial topic. Maybe less so now than back then. But what did you find kind of interesting as you read some of these early biographies as it relates to the idea of having a national debt, the levels of national debt and what do you think some of these guys would think about where we are today? Yeah, so I guess at the end of the day, as a society you make a lot of choices in terms of how many programs you want to be running on the kind of federal or large government side. And that can be debated to this day on either side. I think when you think about the federal debt and how we thought about it, at least in the early history, you have to think about your offsets in terms of revenue and Sammy this gets down to tax, right? When the country started, there is no income tax. So when you think about the federal debt that you have, you have to be able to fund and pay off that federal debt from revenue sources that really only include a few different taxes and it’s mostly tariffs on imports. So you are much more limited on where you can go and you really could default unless you all of a sudden come up with new streams of taxation, whereas today when you can grab a good chunk of the country’s overall earnings, you can support a much larger federal debt. So I’d say a little bit apples and oranges where early in the country’s history you probably should have a lower debt relative to output because your revenue sources are limited, and today to the extent that the Pandora box is open on personal income taxes, and that’s a constitutional amendment that went through in the early 20th century, you can support a much larger federal debt without that necessarily being as concerning. And all the early presidents because of the start that we talked about with Hamilton as secretary of treasury had a national debt until who paid it off, Michael? Jackson, Jackson hated the national debt. Andrew Jackson killed the bank, right? And he killed the national debt. And then by the time his successor, Martin Van Buren, who is, I think we agree one of the least interesting people we read about during this stretch. I mean, the 1800s have some brutal, brutally boring characters to read about. Van Buren really kicks it off, but by the time he’s done in office, we’re back with the national debt. And you talked about, you know, basically revenue sources to cover it. And the other thing that kind of increased the debt over time is with every war, there were higher and higher debt levels. 100%. I think that’s actually the most clear takeaway with the national debt. You see a level that’s established and then you go through a period where you need to finance a war, and you just reach a whole new level. And then it kind of stays up at least at that level or grows a little bit until the next war. So no doubt it’s on the war financing front where you established I’d say a new balance sheet level of debt. Any thoughts on debt or your friend Martin Van Buren or Andrew Jackson before we jump into tariffs, taxes, the revenue stuff that you were talking about. No, I will say so after that first bank of the United States is uncharted they do get a second bank chartered and then that’s the one that Jackson ends up not renewing, taking the deposits from before it ends and putting it into the state banks.

00:20:06 – 00:25:00

I think Jackson has a bit of a reputation as clumsy and this might not be the most thoughtful thing. And I think that while that probably is right at the end of the day, you do want a national bank, we do want the Federal Reserve system – I hope that’s not too controversial, but I do think at that period of time things were a little bit different. So when you think about the Federal Reserve system that we have today, it really doesn’t give loans to individuals, it doesn’t give loans and choose to give money to operating businesses, and those early banks of the United States actually controlled where the credit of the nation was given. So you did have a situation where that entity of the bank had a lot of power in terms of who was able to control capital and I think a lot of what Jackson did ended up broadening our democracy and spreading out where capital was given. So I’ll at least give him some sort of partial credit that it wasn’t just a dumb guy who didn’t like any debt, but saw some problems with the way the institution was structured early on and took things down to be a little bit more again broad based, you could call it a little more democratic. Yeah, and a couple of things on that, I think if you don’t want to go through this journey of reading a biography on each president, which I couldn’t even tell you now, whether I recommend doing it or not, because I think we both independently decided to do this years and years ago and just coincidentally ended up finishing around the same time. Andrew Jackson’s biography. Oh, so good. American Lion by John Meacham. It’s definitely one you should read regardless if you have any interest and then I think you and I were both pleasantly surprised that we enjoyed the Calvin Coolidge biography that we read. And I bring it up because Coolidge is the last president who oversaw an actual drop in the dollar amount of the national debt. And last, World War II took care of that, but he was the last. So those are a couple of books if you’re not interested in kind of going through the whole presidential list. And so jumping over to kind of sources of revenue, tariffs, taxes, things of that nature. I think one thing I’ve talked to you about is you read these biographies and you’re slogging through some of these folks in the 1800s and you’re just the constant debates over tariffs and internal improvements and you just forget sometimes I think we think of tariffs as something that Trump brought up just to go to battle with China like four years ago, but no one really thinks about tariffs other than that. But for the longest time, that’s where we got our revenue. The major flaw in the Articles of Confederation was that there was no legislative taxing power so the constitution fixed that and they decided on tariffs and excise taxes is kind of the easiest way to grab revenue because it was easy to enforce and it would have a nominal impact on the average citizen. One thing I found interesting is that the precursor to the coast guard was created basically to collect and enforce tariffs by Hamilton. And we were not a country of free traders then. There’s definite that wanted to protect and grow the domestic manufacturing base so tariffs help there, which is important to remember if you’re wondering why, you know, we’ve evolved the British policies before independence basically killed any U.S. manufacturing effort so we had a lot of catching up to do. And I recall this tariff started at about 5%, they ended up around 40%, and it really wasn’t until maybe after World War II that we gave weight more to free trade when we thought that would be better for the economy than to kind of protectionist tariff policies. Definitely. And I think it gets, again, to where you’re sourcing your revenue from. One of the things that’s interesting about that is if you just think about collectability. So go back in time and your before social security numbers and companies issuing tax statements and you have to make sure that you match them up. It would have been very hard to actually have done any sort of an income tax on folks at the beginning. I mean, I don’t even know if that’s practical, but if you think about the ability to collect tax, there are only certain ports where lots of goods come in through so you can monitor those parts and you can monitor the goods that come in, and that’s a way that you can actually get your hands around, here’s how I can collect it without being cheated too badly.

00:25:00 – 00:30:02

So I think part of it is almost just physically what can you do to actually monitor and collect stuff, collect money based on some sort of economic activity and early on that’s tariffs, later when you can do that on the income level okay, maybe we don’t want to cause distortions amongst things that come in and you’re able to bring down the tariffs and get more towards free trade. Yeah, and I think the tariffs were really going strong too until prohibition when the loss of alcohol related revenue and the tax there led to the first permanent income tax. We had a brief, I think income tax and other periods I recall during the Civil War, but basically it’s like, hey, here’s this thing called prohibition we’re not going to be selling tons of alcohol to people anymore and taking that tax revenue we better figure out this income tax thing. So prohibition has kind of so many unintended consequences with that. And a great book for that, by the way, is Last Call by Daniel Okrent. I mean, prohibition leads to NASCAR, leads to the income tax, it leads to the mob. I mean, just kind of weird when you think about how boozy we are right now as a society to really think that like a hundred years ago, we basically said, you know, no more alcohol sales is kind of amazing. And you know, to take it back a little bit earlier and I know I’m not a master on this topic anymore saying I said we’ve open doing this for a while, I started in 201, so this is over a decade ago that I actually read Washington and some of the early ones, but the first excise tax roughly would cause a rebellion, right? The whisky rebellion is an excise tax and folks did not like that, didn’t like those internal taxes, didn’t like the taxes on alcohol, didn’t like the taxes on mortgages or other things that were done here. So tariffs seemed like they were the most palatable tax to be able to get through. Yeah, and that was the revenue source until later. Anything else on tariffs or taxes or the presidents that kind of, you know, were dominant during eras where those were interesting topics that you wanted to get into. No. All right. What else were your takeaways kind of as it related to presidential finances or kind of our financial system just as like I said, slogged through some of these, but read through all of these books. Yeah, so I guess quite a bit. A couple of things is I think when we think in our profession about the stock market and the bond market and we’re really thinking about the past 50 years or so, our economy has been so much different before that. The modern idea of a stock market where you sit there and you say, oh, this is what it is and it seems like it’s existed forever. It hasn’t. Very different. Really until you get to Standard Oil, you only have local companies. You really don’t have any national companies, let alone international. So the whole emergence of the current economy is kind of, I would say, always new ground and anytime that you want to say, I can look back at the past and I have a big book of exactly where we are right now, I just don’t think that you do. I think if you look at financial markets before, very different than they are now. The U.S. was a bad credit back if you read House of Morgan, so this is another Chernow, I know Sam, you didn’t like this one it was a tome. When you go back to Peabody, who was before JPMorgan’s dad was in the business over trying to sell American bonds in England and America was not the risk free rate, right? Viewed as junk. So anyhow, as you get to some of the assumptions that we have in current financial markets, it’s not like that’s been the case throughout our whole history, this has evolved quite a bit. And these same topics cycle through and come up again. You know, I said when we were talking about the banking system that, you know, clearly Hamilton was right. I think if Jefferson and Madison were around in 2008, 2009, they’d say, see this is what we were telling you about the banking system basically just took us under and these institutions are too big to fail and you can’t do anything about it. We still have the debate over the national debt and running deficits are still have debates of the right revenue sources. I don’t think we have the gold versus paper currency debate as much anymore, thankfully, but I remember just because maybe, you know, I had periods of immaturity as I was going through these biographies, how clueless some of these guys were and I say guys because unfortunately they were all guys, with their finances. Absolutely. I mean, Jefferson was insolvent. He had to sell his library to the Library of Congress.

00:30:03 – 00:35:06

Teddy Roosevelt was kind of a train wreck financially. I just remember reading how it was almost like if you ever read about Mark Twain, how Mark Twain would constantly go broke chasing these dumb ideas. I felt like Teddy Roosevelt was right there with him. Just not good with his money. And then early on, I mean we talk about, or some people talk about, how kind of corrupt and self interested our system is right now, not anywhere near where things were. I mean, I think in the Washington biography, I think he bought up land around where he knew the nation’s capital was going to be. Let me just go scoop some of this stuff up and the idea of anybody doing stuff like that would give people heart palpitations and heart attacks. I agree, it gives you perspective on some of the stuff that you’re going through that it’s not so unusual, it’s been the case for quite a while. So another one I find interesting is Grant who basically, because he had not been successful outside of the army and then the army, the Civil War, General after the Civil War, the presidency, by the time he’s done as U.S. president-and he also gets in trouble by trusting some people that he shouldn’t have trusted and investing in some ventures and going completely broke-since we didn’t have a pension at the time for presidents, his finances were just in horrendous shape to the point where, remind me, but he basically had to crank through a memoir in short order while not doing very well just to basically leave his wife and family on good financial footing after he was gone. Yeah, it’s amazing to think that you could have a president and a very, very important general in our history who essentially ends his life struggling through cancer and trying to finish his memoirs to just be able to support his family. Yeah, and I think another oddity on that is I think Mark Twain might have been his publisher or something like that. It was like one of Mark Twain’s only published books. I think I didn’t go well and Mark Twain’s whole publishing thing went down, but Grant was maybe the one successful one that actually went through Twain. And we didn’t include the Grant memoir in our list of presidential biographies in that blog post I referred to, but it is a good read. It only goes through the Civil War, it doesn’t go into his life as president, but another thing to check out. So Michael with that, you know, I think this has been a fascinating discussion. Hopefully people get a lot out of it. I always like to wrap up the podcast with two questions. The first is, what’s one thing our listeners who are mostly long-term investors can take away from this discussion about history, even if they don’t read anything more about this topic. Yeah. So that’s an interesting question. I guess the takeaway that I would have is I think through American history, we have a very dynamic system and you end up bouncing back and forth between different political parties. And I think you tend to, in the present time, always think that you’re in an extreme. And if you’re a long-term investor, I think it’s important not to get thrown off by our system that does gyrate from side to side. But in the long term, you really want to make sure that you’re invested through it all. Absolutely great stuff. And then since the name of our podcast is called wealthy behavior, what’s one wealthy behavior that you practice consistently that you’d recommend to our listeners? Well, I guess I guess I got to give you two. So one will be more of the standard type and that’s saving early and often. So I think when you think through what type of people end up succeeding, when you put away money when you’re young, you look 30, 40, 50 years down the line and that 6% return comes out to something like a 50% return on the initial dollar. So that extra period of time matters a heck of a lot with compounding. And then outside of that mathematical side of me, I would say, wealthy behavior is invest in yourself. So I’m going right along with this podcast, reading and learning from the experience of others in the past, it’s a great use of time. It’s worth a lot of money to make good decisions so learning from others and making good decisions based on what they did is a significant hand up and it makes you more valuable in the workforce and more valuable to your company. So read and invest in yourself. Those are two great ones. Thanks a lot for sharing Michael and thanks for listening everyone.

Thank you for listening to Wealthy Behavior. If you found the conversation useful, please consider leaving us a review wherever you listen to your podcast and sharing this episode so those around you can live a rich life too. For more insights, subscribe to our weekly blog and heritagefinancial.net and follow heritage financial on Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn. Check out my personal finance blog at thebostonadvisor.com. This educational podcast is brought to you by Heritage Financial Services, LLC located in the greater Boston area.

00:35:07 – 00:35:28

The views and opinions expressed in this podcast are that of the speaker, are subject to change and do not constitute investment advice or a recommendation regarding any specific product or security. There is no guarantee that any investment or strategy discussed will be successful or will achieve any particular level of results. Investing involves risks including the potential loss of principle. *This automated transcript may contain grammatical errors.

About Wealthy Behavior: Heritage Financial Services

Wealthy Behavior digs into the topics, strategies, and behaviors that are key to building and protecting personal wealth and living a rich life. We’re Boston Massachusetts-based wealth managers who have been helping busy, successful people pursue their financial goals for more than 25 years. Hosted by Sammy Azzouz, President & CEO of Heritage Financial, Wealthy Behavior digs into the topics, strategies, and behaviors that are key to building and protecting personal wealth and living a rich life.